When the family lived in Sweden, they followed the Swedish practice where a man’s children use his given name plus the suffix "-son" or "-doter" for their surname. Thus Ander’s sons were called "Andersson" and Olof’s daughters "Olofsdoter". However, after they moved to America they all adopted the surname "Holm" which means "islet" in Swedish.

A chart provided by Wayne Olson shows Holm ancestors in Svarteborg and other locations in Sweden, going back to the mid 1600s.

The earliest ancestor mentioned in Helen Hobert’s book is Anders Anderson who lived from 1769 till 1831. His wife was Helena Olsdotter and she is said to have been born in 1774 and died in 1861.

|

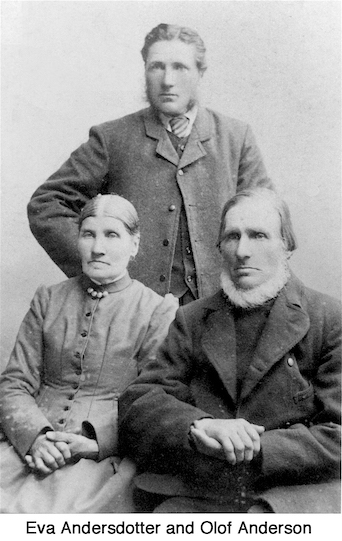

Olof Anderson (1815-1892) was a son of Anders Anderson. He married Eva Carolina

Andersdoter (1824-1907). They are reported to have had nine children but the names of only

six of them are known from the family tree. These six are: Anna Maria (1844-1936), Karl Johan

(1846-1914), Anders (1848-1917), Alfred (1851-1926), Fredrik (1853-1930), and Otto

(1862-1954).

Olof Anderson was a farmer who had had three large farms with cattle, horses, and other animals. Olaf and his first three children were born at a farm named Dufveskarr in the Svarteborg parish. Unfortunately, he lost two of the farms by co-signing loans for several other people. He was left with a farm named Helgebo or Häljebo on the shore of Lake Bullaren, the largest lake in Bohus Län. Häljebo is sandwiched between the eastern shore of the lake and a rocky hill. The fields are strongly sloped and a small stream flows through the farm. The family’s church, Mo Kyrka, is located on the other side of Lake Bullaren. Häljebo’s latitude and longitude is 58º 39' 31.16" North, 11º 34' 34.64" East and its location is shown on on this map. Olof and Eva’s daughter Anna Maria remained near where she grew up and married Olof Långström. Augusta (1867-1935), Axel (1868-1935), Carl Johan (1871-1944), Gustaf (1873-1956), Anna (1875-1949), and Mathilda (1888-1949). Some of their six children remained in the area, some moved to Norway, and Gustaf moved to southwest Minnesota near his uncles. Anna Maja died in 1936 and was buried in the Mo church graveyard. Her daughter Mathilda and grandson Harry were buried next to her. Olof and Eva’s son Carl Johan remained in Sweden and changed his last name to Holmberg. He and his wife, Julia Tollesdotter, had thirteen children: Karl (1870-1888), Tekla (1872-1947) Gustav (1874-1953), Anna (1876-?), Anders (1877-1951), Hartvig (1880-1936), Anna (1883-1958), Gerda (1885-1980), Henrika (1887-1915), Jeanna (1890-1969), Ernst (1891-1962), Alma (1894-1970), and Helfrid (1898-1979). They lived at first in Grimåsen, not far from Häljebo, but later moved to Romelanda Parish, which is close to Göteborg.

|

|

|

|

Carl Johan’s son Hartvig Emanuel Holmberg immigrated to St. Paul, Minnesota, in the fall of 1910. Carl Johan’s grandson Ernst Ingvar Holmberg, the son of Ernst Victor Holmberg, became a sailor. He married a woman in Houston, TX, and he tried to sneak her back to Sweden as a stowaway. They were discovered and got tossed off the ship in New York. They worked for a while on the Swedish liner Kungsholm, but settled in the U.S. after WW II made transAtlantic shipping dangerous. Olof and Eva and three of their children immigrated to the U.S.A. The first of Olof and Eva’s children to come was Anders (or Andrew) who was a sailor. He came to the U.S. in 1872. In 1878 he married Annie Peterson in Wisconsin. She was from Denmark. The next year they moved to southwestern Minnesota. Andrew and Annie had five children: Olivia (1878-1887), Mary (1880-1978), Eva (1884-1979). Hattie (1888-1973), and Carl (1890-1988). In 1887, he was managing a farm in Murray County in southwest Minnesota. The owner of the farm came out to hunt, and accidentally shot and killed Olivia. Andrew quit and bought his own farm near Tracy. Annie died in 1897 and in 1899 Andrew married Kate Johnson. Alfred Olofsson married Johanna Gudesdotter in Sweden in 1874. They had six children: Olivia (1876-1944), Gerda (1877-1935), Oskar (1880-1906), Alida (1884-1969), Bernt (1887-1876), and Johan (1890-1977). In 1891 Alfred Olofson arrived in Minnesota with his three oldest children. By 1900, he had saved enough money to send for his wife and his other three children. They voyaged by ship to Montreal and then by train, first to Chicago and finally to Tracy. When they arrived, they were surprised to greeted by crowds, bands, and fireworks. Later they learned the festivities were for the 4th of July, not for them. Son Fredrik Olofsson remained at Häljebo. His story is in the next chapter.

|

|

Andrew was followed to America in 1882 by Otto who settled near him. Otto took over the management of the farm that his brother Andrew had left after Oliva was killed. Otto married Caroline Anderson in October 1887. They had six children: Oscar (1988-1978), Victor (1891-1975), Albin (1894-1982), Arthur (1896-1969), a stillborn in 1902, and Irene (1906-1997).

In 1892 Olof and Eva themselves arrived in the U.S., but Olof died a few days later on August 20, 1892, and is buried in Bethany Cemetery in Murray County, Minnesota.

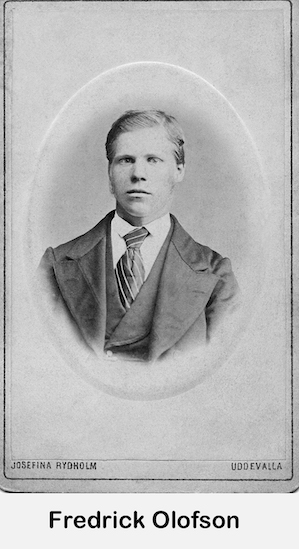

III. The Fredrik Olofsson Family

|

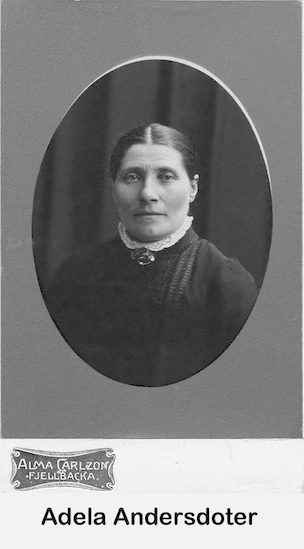

Fredrik Olofsson, son of Olof and Eva Anderson, remained in Sweden. He married Adela

Anderssdoter (1853-1941) around 1873.

Adela’s family had homesteaded in the timberland of Varmland Province during the reign of King Karl IX (also known as Charles IX). Her name would have been Adela Thorn, but her mother was not married when Adela was born. She was taken in by other people when she was three years old. She had to work when she was only five or six, and had only six weeks of schooling. Her mother eventually married an man named Hans and they had three sons. One son was a sailor and drowned in the English Channel. A second son, Karl Johan Hansson, immigrated to Canada and worked in the gold mines by Lake of the Woods. After many years he went back to Sweden and died. The third son, Hilmer, homesteaded in Minnesota. He worked and died in an iron mine, leaving his wife and two small children, Evelyn aged eight and Arthur aged four. Fredrick and Adela Olofsson had ten children: Hanna Kristina (1876-1879), Victor (1879-1967), Herman Gottfred (1881-1885), Hanna Mattilda (1883-1899), Maria (1885-1962), Anna (1888-1967), Emma (1891-1908), Herman (died in infancy), Karl (1895-1979), and Alida (1898-1986). Only half of them lived to be adults.

|

|

|

Fredrik Olofsson worked as a farmer and a quarry worker. He had a very small farm with a cow, sometimes a calf, a couple of sheep, and some chickens. The family sold eggs. They also grew wheat, rye, clover, berries, and vegetables. Wild berries grew in abundance. Still, they had to work hard to make a living.

Much of what they ate was from their own farm or produced locally. For breakfast they might have eggs laid by their chickens, bacon from the pigs they raised, and homemade bread, butter, and jams. At the noon meal they might have fried "palt" (a potato dumpling), bloodwurst, "korv" (a type of frankfurter), bacon, herring, cheese, porridge, and bread. In the evening typical foods were chicken, lots of seafood such as herring, mackerel, and lobster, vegetables such as carrots, tomatoes, yellow peas, potatoes, turnips, and cabbage, milk and cheese, apples and pears, and all kinds of berries including strawberries and blueberries. Yet, despite the variety of good foods, there was not always an abundance. Sometimes they had nothing to eat but bread dunked in fish broth.

One indication of the difficult economic times the family had is that at least one of the children was sent to work outside of the home. When Anna was about eight years old, she went to live in another family’s home to look after two girls and the family’s cows. The pittance she earned was sent home to her family. On one occasion when her employers left her alone with the girls, one of the girls began to cry. Nothing could be done about it so that when the employers returned, they found both girls and Anna sitting there crying. The woman was compassionate and comforted all three of them.

After the start of the twentieth century, the children of Fredrik and Adela began to follow the previous generation to North America. Maria came first in 1904 with her bachelor uncle John Hanson, who was a younger half-brother to Adela and who had no family of his own. In their journey they passed through England where she had her first taste of exotic fruits such as bananas and oranges. She settled in Kenora, Ontario, which had previously been called Rat Portage for the muskrat trade that had been important to its economy. Anna in 1906 and Emma in 1907 joined Maria in Kenora.

Maria married August Anderson and they had a daughter, Agnes, in 1907. Then disaster struck. An epidemic, probably cholera, took August in May 1907, the baby Agnes in September, and sister Emma in January 1908. Maria remarried in April 1908 to John Samson, and they lived out their lives in Kenora. Maria and John had eight children, including twins: Arnold (1909-1945), Harold (1910-1982), Ebba (1913-1976), Ella (1914-?), Aina (1916-2016), Alf (1920-2003), Mabel (1920-1990), and Clarence (1925-1982)

Anna married August Carlson. They had four children: Dagmar (1909-1999), Errol (1910-1984), Victor (1912-2000), and Eleanor (1924-1996). Anna working as housekeeper nanny. Her eldest daughter, Dagmar Marthy Carlson, was named after a little girl she cared for, Marjorie Baxter. August worked for the Canadian Pacific Railroad. In 1928 when he was 44, he was acting as switchman in the railyard. A train was coming in, and he stepped from one track across to another to get out of the way. He didn’t hear another train coming in from the other direction. He was killed instantly. After his death, Anna was granted a $50 per month pension, as well as a lifetime pass on CPR trains and ocean liners. She moved to North Vancouver around 1941. She enjoyed traveling. She took a trip to Hawaii once. Later, visiting her brother Karl’s camp at Willard Lake, she told about going out on a catamaran and learning to do the hula. She gave a great demonstration...singing along with her dance. She was full of spirit! In later years, at a Christmas celebration, Her sons started to tease her about knitting all the time because she was now an old lady. Anna was perfectly capable of holding her own when her sons teased her, and she said, “I’ll show you that I am not old!”. She changed into trousers, went into the center of the carpet, and stood on her head.

Anna’s sons Victor and Errol were members of the Kenora Rowing Club’s team which won the Sir Thomas Lipton Cup in 1930. Victor Carlson won two more gold medals in l932 and l936. He also was a ski jumper in Kenora until he damaged his back on a fall.

Anna’s son Errol Carlson joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Vancouver. Because he was Swedish-speaking, he was asked to go to Sweden to what he called a Jehovah’s Witness commune. Errol was the only one of our relatives who moved back to Sweden. He lived out the rest of his life in Sweden, although he returned periodically to attend the worldwide congress of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Brooklyn, NY.

Victor followed his sisters to Kenora in 1909. Victor and his family did not remain long in Canada, moving to the USA in 1917. His story is in the next chapter.

Fredrik and Adela’s youngest boy, Karl Johan, had his first job at the age of 5, working for the local blacksmith. It was the only job he was ever fired from, because he was too small to work the bellows! He was sent to work for a neighbouring farmer. He lived there for a year, and was given room and board, and a new suit of clothes at the end of the year. His daughter said he had a soft spot in his heart for animals, that when he was a little boy and it was time for slaughtering the pigs, he would run away early in the morning and hide away for the whole day. He started work in the rock quarries at the age of 12.

Karl emigrated to Kenora in 1913. In the early 1920s, he returned to Sweden temporarily to build a new house for his parents. Back in Canada, he married Violet Whiteman in 1929. She had been born in Fort William on Lake Superior and had lived in Kenora since she was eight. They had two daughters and one son: June (1930-2007), Charlotte (1933-2017), and Carl William (1942-present). In addition to working at paper mill Karl operated a resort, Karl’s Place, on Willard Lake.

At some time, Fredrik, Adela, and their youngest children left Häljebo and moved to a new farm, Hällekårret. Hällekårret was in the country, about five minutes from the nearest neighbor and from the road which ran between Kville in the north and Hamburgsund in the south. There were fir, pine, and birch woods all around, and they cooked and heated with wood they cut on the farm. The farm was up high so that they had quite a view of the neighbors’ houses, of the school and the church, Kville Kyrka, in Kville about a half hour journey away, and of the mountains and high hills of that region. There were several large ponds in the neighborhood, where the children skated during winter. They had one well near the house that was used for cooking and drinking and a more distant well that was used to refrigerate dairy goods. There were several large boulders in the back of the house on which were carved runes from an earlier settlement.

By 1940, Häljebo was owned by Karl Olausson. At the time, it covered 185 acres and was worth 10,700 Swedish Krona.

The youngest daughter, Alida, married Adolf Karl-Johan Schevenius in Sweden. They had one child, Gunborg Alvina Schevenius. Around 1930 Adolf Schevenius emigrated to New York City and changed his name to the more American-sounding “John Adolph Carlson”. In Sweden he was a quarry man but in America he made good money carving grave monuments.

Fredrik Olofsson never did go to North America. An old man with a long white beard, he died in 1930. Two years later, his wife Adela and daughter Alida moved to America. Adela lived with her daughter Anna in Kenora.

Not going in the middle of the continent like the rest of the family, Alida joined her husband in New York City with her daughter, Gunborg. Gunborg legally changed her name to Margaret “Peggy” Alvina Carlson. Alida’s husband soon left his family during the depression. At first, Alida struggled, but things improved when she got a job as a Swedish tutor and nanny for the children of Nathan Vasa, a pharmacist who owned a chain of drugstores. Peggy married Allan Holway in Oct 1943 in New Orleans, Louisiana.

In 1936, there was a family reunion in Kenora with Victor and his daughters returning from Michigan for a visit. Alida and Peggy came from New York. Maria, Anna, and Karl were also there with their families.

Eventually Adela broke her hip and was confined to the hospital for an extended stay. She died on December 9, 1941, the day she had been scheduled to be released.

Victor Holm, born in January 1879, was the oldest surviving child of Fredrik and Adela Olofsson. In the spring of 1884, he became seriously ill and was confined to bed and was sore in every joint. The nearest doctor was in Fjällbacka about 50 kilometers away and the family may have lacked money to pay a doctor anyway. But a kindly army medic came by and prescribed wrapping unwashed sheep wool round the joints, and salt water baths and lampante oil. Victor was so sore so they had to wind him into a sheet. He became unconscious for an unknown length of time. It was spring when he woke up and the sun shone into the cabin.

When he was 16 years old, he started to work for local farmers. In his words:

“In summertime up at 5 am and to bed 10 at night. I had 30 pigs to feed 3 times a day, 2 horses, 8 cattle, some sheep, plowing, fencing, bring wood, 1 time a week to the mill, haying, and cut the grain. I did not milk the cows. For this I get paid 7 kroner a month or 1 dollar 6 cents a month. Next year I got 150 kroner a year, and my parents bought a cow and paid for it 70 kroner cash. Then I went to a brickyard in Norway. The first summer I just made it go, but next summer I came home with 400 Norwegian kroner and gave to my parents.”

On 24 September 1900, “Viktor Emanuel Fredriksson” enlisted in the Swedish army as a rote soldier in the Royal Bohuslän Regiment (17 Infantry) Tanum Company. As a rote soldier, he had the option of being provided with a a small homestead and farm with additional support from local farmers or of getting an annual salary of 200 kronor. We don’t know which option he selected. He also received a signing bonus of 40 kronor. His assignments are not known but it is said that he sang cadence for the marching soldiers and there is a photograph of him and a number of his comrades taken in 1904 at Norrkoping, on the Baltic Sea coast south of Stockholm. He was happy with the education he got as a soldier, learning mathematics, geometry, geography, cartography, proper essay writing, Morse code, fast writing, Esparanto, and Italian double bookkeeping. During his service he was promoted to sargeant.

In December 1906, Victor married Frida Sörkvist, who was 18 years old at the time. He was still in the army.

|

Frida was the daughter of Carl Sörkvist and Hilma Fredriksdotter. Carl Sörkvist’s family was from Kville Parish. His father was called Mattias Nilson and his mother was Augusta Johansdotter. Carl Sörkvist was born in Svarteborg in 1852 and died in 1929. Hilma’s father is thought to be Fredrik Goranson and her mother was Eva Gabrielsdotter (1829-1920). Hilma was born at Bramarken in Krokslad Parish in 1850 and lived till 1941. Frida had six brothers and sisters: Matilda (1872-?), Johan (1875-died in Norway), Gustav (1879-?), Hanna (1882-?), Karl (1885-1900), and Emma (1892-?). Carl Alfred joined the Swedish army Oct 01, 1870, when he was 18 years old. He left the Army Sept 10, 1901, as a Lance Corporal. When Carl Alfred left the army, he became a forester. He was very kind and let people take wood from the forest. Therefore, the owner relocated him to a more remote area, which today is more or less within Uddevalla’s city borders. Carl became gamekeeper in 1905. The earliest ancestor that we know for Hilma Fredriksdotter is a soldier Petter de Moine, who originally was from France. Petter served in the Swedish army. He was killed during July 1702, fighting Russians in what is now Estonia during the Great Northern War. One of Frida’s relatives traced the female descendents of Petter through the centuries to the present. You can see it here. Frida’s maternal grandmother, Eva Gabrielsdotter, was imprisoned for a year at Uddevalla in 1876. She was convicted of counterfeiting and fraud for having approved bail that she knew to be false. At the time she had been tax clerk in Svarteborg parish. At that time, Frida’s mother, Hilma Fredriksdotter, was 25 years old and already was married to Carl Sörkvist. In later years the Svarteborg parish registers sometimes recorded Eva as being homeless. |

|

VI. Victor Holm and His Family

Victor and Frida soon had a daughter Svea (1907-1946). Victor left the army and intended to get a municipal job at Strömstad, city on the border with Norway. Unfortunately, someone else had gotten the job ahead of him. Therefore, he decided to follow his sisters to America. He may have expected a more prosperous life in the new world, but little could he know that there would also be much hardship and long separations from his family. In June 1909, temporarily leaving his wife and daughter in Sweden, Victor left for America. The first leg of his journey took him from Göteborg to Grimsby on a ship named Rollo. Then he traveled by train across England to Liverpool. There he joined 1,188 other passengers on the 14,500-ton steamship “Empress of Ireland” under the command of Captain J.V. Forster. The ship was 570 feet long and 65 feet wide. They left Liverpool on Friday evening, June 18th. There were moderate gale winds from the west and heavy seas on the second and third day of the voyage. Eventually the weather lightened and the ship arrived at Rimouski, Quebec, after 6 days at sea. From there the ship sailed on to discharge its passengers at Quebec City. (Five years later this ship struck a Norwegian collier in the St. Lawrence River and sank with a loss of 1014 lives.) One of the first things Victor did in Quebec was to send a postcard home to Frida. He then continued on to Kenora by train to obtain work and to build a home for his family.

In Kenora, Victor first lived with his sister Maria and her husband John Samson, but he did not spend much time there. Mostly he lived in work camps. Work was dangerous. Twice he was nearly hit by trains. Once, way out on the ice of Lake of the Woods, he sliced his foot with his ax.

On May 13, 1910, Frida and Svea, then about three years old, arrived in Quebec to join Victor in Kenora. Victor hadn’t expected them to come as early as they did and his home wasn’t ready yet. So Frida had to live with her sister-in-law for several months. Frida was soon pregnant and the family grew with two more children, Aurora born in 1911 and Carl in 1913.

Victor saved some money and bought 172 acres of land along the Winnepeg River north of town, next to land bought by his brother-in-law, John Samson. Around this time, Victor’s younger brother, Karl, came to Kenora from Sweden, and helped his brother with his home construction.

Their home, which was near Anna’s and Maria’s, was at the top of a steep slope. It had only two rooms - a combination kitchen and living area, and a large common bedroom. In the back of the house was a big rock. Down below it Victor built a shed with a sleeping room above it for the growing family. To get to the main part of Kenora five or six miles away, they walked along a wooden sidewalk on the shore of Lake of the Woods. They had to carry many of their staples long distances. Water came from a tap at the bottom of the hill. Victor carried it up to the house in two pails slung from a shoulder yoke.

- Years later Aurora wrote,

“My father was a typical Viking-type individual--blond,

blue-eyed and strongly built, and very kind and good to his family. He was a

lumberman, and his work required him to be away from home many days at a time out in

the woods. He had a big, blond moustache of which he was very proud. I can remember

when he came in from the cold...there were icicles and frost around his moustache...those

frosty kisses were something very special!

- “In contrast to my father, my mother was olive-complexioned, brown-eyed, slender and tall. She was quiet and gentle, and devoted her whole life to her family. She would stay up late many evenings, sewing or mending clothes, fixing our dolls, and doing the many things that only a mother can do to care for her family. She had one of those old knitting machines, and she knit all our stockings, mittens and sweaters on it for us. We used to help put the arm on the spool for her. She was the only one in her family who left Sweden, and she was only 21 years old when she came here, so I am sure she must have been lonely for her family at times even though she never mentioned it.

- “We had neighbors who had children just about the same age as we were. I can remember in the summer when we used to have severe electrical storms. My mother and the neighbor lady used to get all the kids together and stay up all night watching so no harm would come to us. Also we used to go to the neighbors to get our milk and carry it home in a tin pail. One time I went up to get the milk, not knowing they had the measles--well, sure enough, a few days later I came down with the measles--then the rest of the kids got them too!

- “I was just like my mother’s shadow and had to be with her all the time. One day, when she was doing dishes, I was up near the counter and fell down and broke my arm. We didn’t go to doctors in those days, so they put my arm in a sling and let nature take care of itself. To this day, I have a lump on my arm from this fall. And then there was this darling kitten we had for a pet. We used to dress her up in dall clothes. Then we would put her in the buggy and she would sleep there all day.

- “We were surrounded by Indians where we lived. The only word I can remember is ’BUSHOO’ which means ’Hello’. They lived like Gypsies, wandering around the country side. I can remember seeing them by the lake, scrubbing clothes, fishing, or just congregrating together. Every so often they would come to our house and want to trade their beadwork for articles like matches, root beer, etc. For many years I’ve had a hanging pin cushion that was made by them with the year of my birth on it--all done in beads.”

- “In contrast to my father, my mother was olive-complexioned, brown-eyed, slender and tall. She was quiet and gentle, and devoted her whole life to her family. She would stay up late many evenings, sewing or mending clothes, fixing our dolls, and doing the many things that only a mother can do to care for her family. She had one of those old knitting machines, and she knit all our stockings, mittens and sweaters on it for us. We used to help put the arm on the spool for her. She was the only one in her family who left Sweden, and she was only 21 years old when she came here, so I am sure she must have been lonely for her family at times even though she never mentioned it.

At Christmas they had a tree which was decorated traditionally with candles. One year, Svea came too close to the candle and her dress caught fire. Fortunately she survived.

Victor and Frida did not attend church regularly, but the children were baptized Lutheran and the two girls attended Sunday school. When Victor did attend church, he filled the whole church with the powerful sound of his singing. Throughout his life, he enjoyed singing.

In August 1916 Victor crossed into the U.S. at International Falls, Minnesota, and wound up in Victoria, Michigan, in November and December. After he found that he could work there in the copper mine, he returned to Canada for his family. On April 9, 1917, he crossed at International Falls again to emigrate. Three days later Frida crossed from Rainy River, Ontario, to Baudette, Minnesota. They and the three children took a train to Victoria.

They found a home there which was some distance down the road from the mining location. Water for drinking and other household purposes had to be carried by hand from a stand pipe at the bottom of the hill by the house. There were no paved roads or streets. A man who owned a store in Victoria delivered groceries and staples to the residents of Victoria using a horse-drawn wagon. He was married to a sister of the Norwegian arctic explorer Roald Amundsen. They became friends of Victor and Frida.

Victor wanted a more satisfying life with the earth so, in 1919, they moved to a rented farm in Port Wing, Wisconsin. This was fortunate because two years later the high demand for copper caused by World War I ended. Then the mine at Victoria closed and the rest of the miners left, abandoning their log houses and apple trees to the occasional wandering black bear.

The family continued to grow on the farm at Port Wing. Their little home had three rooms downstairs and one big room upstairs; they filled the house. The last child, Greta, who was also called Gretchen, was born there in 1920. They acquired a large black Newfoundland dog, named Nigger after his color. The dog lived with the family 15 years.

On the farm they grew corn, potatoes, carrots, peas, strawberries, and apples. Frida and the children did much of the work. They made hay for the cows, and cut and shocked the corn. The children watched over the chickens so that hawks would not eat them. At first they had no horse so Frida had to pull the hay rack. Later Victor got an old black horse. The horse was used to pull a stone bolt to haul rocks and the children would ride on it. They picked the big red strawberries and sold them for 10 cents a quart. The strawberries and eggs were also traded for staples such as coffee, flour, and sugar. The children carried drinking and cooking water home from a spring; water for washing clothes, taking baths, and washing hair was collected from the roof in big rain barrels.

The older children attended South Shore Community School at Port Wing. Since Swedish was spoken at home, this is where they first learned any substantial amount of English. They lived about 4 miles from the school, and were carried to and from school in a horse-drawn covered wagon. This is believed to be the first free transportation provided by a school anywhere in the U.S. A replica of the wagon is still displayed at the Port Wing town square. During the months when snow covered the ground, the wagon was converted into a sleigh. To keep warm, every child had a brick that had been heated in an oven and wrapped in paper to put by his or her feet. At school, the bricks were kept in another oven for the trip home. Sometimes wolves would follow the wagon in the cold winter twilight to and from school; the driver carried a rifle for insurance against their coming too close.

Unfortunately the farm did not do well enough to provide for the family. When Victor heard, through a friend, of work in Chicago he went. While there he worked as a rough carpenter and a mason helper for a contractor. One season in Chicago, his foot was injured by being run over by a wheelbarrow of cement. By winter 1922, the situation had become very difficult though they still had food such as “sylta”, a preserve made of hog’s head and beef. They had a Christmas tree, but there was no money for presents. Fifteen-year-old Svea was told to tell the other children that there was no Santa Claus. Three days after Christmas, on Thursday, December 28, Victor started work near Iron River, Michigan, at the Rogers Mine, operated by the Munro Mining Company.

In August 1923 Victor was ready to bring his family to Iron River. He came for them in a brand new 1923 Model T Ford touring car with side curtains, running boards, and a luggage carrier. On August 23, the two parents, four children, and Newfoundland dog all piled into the car for the 200 mile trip. The journey took 12 hours on the roads of that day with mud sometimes up to the hubcaps. Victor had never driven before and his arms were stiff when they finally arrived at their new home, a mining company house near the corner of Rogers and Second Streets in Rogers Location, Bates Township.

There were some changes in diet from what the old folks had had in Sweden. A typical breakfast could have oatmeal, cream, bread, butter, and milk. Lunch might be vegetable soup, bread and butter, rice or tapioca pudding. For dinner they might have meat balls, roast beef, or swiss steak, potatoes, bread and butter again, milk, and coffee.

Around 1925, Frida’s health began to deteriorate.

It became progressively worse.

In March 1928, she wrote a letter home to her parents.

She wrote about her children.

Svea was working in town as a bookkeeper.

She walked more than three miles to and from work every morning and evening.

Aurora, Carl, and Greta attended school and came home for dinner, the noon meal.

Aurora helped with cleaning and washing. Carl brought in the coke and wood for the fire.

Frida wrote about the weather.

“Here is snow over all and snowdrift so high as houses in some places, but now for some days it is thaw so it will go away this year too. This winter has been long. In October the winter began, many snowstorms and very cold, more than -40 degrees celcius. But here where we live now is calm and nice, big trees around the house ... I have not been cold this winter, because we had coke for the stove.”

And she wrote about her health and her husband.

“They are all in good health but I am not. I suffer from this and that. This night I couldn’t sleep because of stomach pain. Sure it is gout as Hedda use to say. Above this I have rheumatism here and there, and cramp in my legs, very bad sometimes... Then I must tell you that V. Holm has been terribly evil to me since I was ill. He has never been kind, but I didn’t tell you before. He never allowed me to rest, not even on Sundays. When I was tired he said that I will rest in the grave. You see, that’s because I have been so ill. I have been so stupid and tried so hard that he should be content, but he was never satisfied. Since I became ill and couldn’t work so hard he abused at me and always said that I was lazy and rotten.”

Frida ends the letter with

“Don’t be sorry for me now, there is no danger for me now, my life is better now than it was since I was married.”

A month after writing this letter, Frida died at home. Greta was 8 years old, Carl was 15, Aurora was 16 but would turn 17 in four days, and Svea was 20. Her death certificate said she died of organic heart disease. Her funeral was held at home with services by the Rev. Carl Olson of the Swedish Mission Church of Stambaugh. Burial was in the Bates Township Cemetery, on the west side of the Bates-Amasa Road.

A year before she died,

Frida had recorded the following message in Aurora’s autograph book:

When you’re up against a trouble meet it squarely face to face; lift your chin and set your shoulders, Plant your feet and Take a brace. When its vain to try to dodge it, do the best that you can do: You may fail but you may conquer See it Through! Black may be the clouds about you And your future may seem grim, But don’t let your nerve desert you Keep yourself in fighting trim If the worst is bound to happen Spite of all that you can do, running from it will not save you. See it through. Even hope may seem but futile, When with trouble you are beset. But remember you are facing, Just what other men have meet You may fall but fall still fighting don’t give up, what’er you do Eyes front, head high to the finish - See it through!

Soon after Frida’s death, the depression arrived. There were times when Victor worked only 8 days a month and was paid only $1.50 per day. Out of this he had to pay $3.00 a month for electric power. Still the family had its own cow and a garden so that there was always some food. Potato soup was a common meal. In July 1934, Carl joined the Civilian Conservation Corps and sent home $12.50 out of his monthly pay of $17.50 to help feed and care for the family.

Their big, black dog, Nigger, did his share as a provider too. During the winter many people hid food outside in their wood piles where the natural refrigeration kept it fresh. In his wandering around the neighborhood, Nigger picked up hams, beef, and other meat and brought them home. One day he dragged home a whole washtub full of food. These activities, of course, did not make him very popular with the neighbors. In addition most of the puppies born in the location in that era turned out to be black. Not surprisingly, he was shot at a lot of times and had to have some bullets removed. Nigger also helped to protect the house. One day a squirrel got in to the house, and Nigger gave chase. Curtains were pulled down and other things knocked over all through the house.

In July 1927 Victor officially declared his intention to become a U.S. citizen. He satisfied all the requirements in February 1931 and was granted citizenship on June 27, 1931. His children were naturalized at the same time.

In the mine, Victor alternated two weeks on day shift and two weeks on night shift. His

bedroom was off the kitchen so when he worked night shift, the children had to be quiet so as

not to wake him. When on day shift, he woke up hard; the children used to take turns trying to

get him up in the morning. Because of his strength and courage, he was assigned hazardous

jobs. Years later he wrote:

- “Lots of time in the mine I stood on the ’brink’ of the grave and what should of happened to my children? I never mentioned I was in danger and had to take ’dangerous’ jobs there nobody wanted to take”.

Victor was very strong and self-confident. He thought that he could lift anything if he could get just one end of it off the ground. But this view failed him one day when he managed to raise one end of a Model T engine but the bulk was too much for him.

Despite earning a living from his job in the mine, Victor still wanted a farm of his own. The day after Christmas in 1930 he bought 20 acres on the Passamani Road near 28 Lake from the Campbell-Van Ornum Company. After working a day in the mine, Victor would go to the farm to clear land as long as it was light. Together with Carl, he cleared enough land to put in a garden. Because they did not live on the land the garden was vulnerable to raiding. One day in 1934 Victor caught Aurora, cousin Peggy Carlson, and others from the location in the act.

Construction of the house started in spring 1939 after Victor and Carl had built a chicken coup in which the family lived while the main house was built. By late July, they had erected the basic shell but the roof was still to be added. The building took a long time; some exterior work still was unfinished in 1940, and it wasn’t until between 1942 and 1944 that siding was added. An early picture shows a small windmill at the peak of the roof. The windmill ran a generator, which charged an array of 6-volt batteries to provide some electricity for the house. Once when the wind blew hard and the sound of the generator could be heard inside, Victor referred to it as “that S.O.B. screwing in the wind”.

In 1944 or 1945 a tall flagpole was added in front. Every morning Victor displayed the American flag from his flagpole. On Memorial Day and other special holidays, it was flown at half mast. On June 21, which is a Swedish holiday called Mid-Summers Day, he flew the Swedish flag beneath the American. On that day too, there was always a picnic for the Swedish emigrants at the Erick Ohlsson home near Sunset Lake.

Commercial electricity was brought in to the Passamani Road shortly after the end of World War II. Victor worked at clearing brush from the side of the road so that the lines could be brought in from US2. Aurora had come home from Duluth during this period when Carl was in Saginaw and Greta in the tuberculosis sanitarium. He was grateful for the company and the coffee and water she brought him along the road. When the power line was connected, he quickly got rid of all of his kerosene lamps.

The animals Victor had on his farm were more pets than anything. Greta named one of the pigs “Poopadia”. One day a cow managed to get her head and front quarters into the kitchen entrance. The only way they could get her out again was to lead her right through the house and out the front door because she couldn’t be turned around inside. He also had dogs. The large black dog, named Nigger, that the family obtained when they lived near Port Wing in Wisconsin was mentioned above. Victor’s son Carl loved that dog and remembered him decades later. Victor got Lucky, a German shepherd, as a pup in 1940. Pojke who was a mongrel who came after Lucky died in the 1950s. “Pojke” is Swedish for “boy”. Victor's last dog was Sputnik, who was Pojke’s son.

In 1947 Victor retired from the mine. He celebrated by visiting his old homeland for a long visit. He arrived in late April after a cloudy, foggy, and uneventful crossing of the Atlantic. Hamburgsund was especially cold and windy that year, but soon he experienced much excitement visiting with old friends and relatives. He was pleased that some of his old army comrades knew who he was right away. One day he went fishing on a boat on the sea and caught a squid. When the squid was pulled into the boat, it let loose with a spray of black ink. What a surprise! Then in October he married an old aquaintance, Jenny Augusta Soderstrom. One story is that they bicycled around in Sweden. He then returned to Michigan as his visa was up, temporarily leaving Jenny in Sweden.

During December of that year, Victor was cutting firewood in the woods behind his house with a buzz saw he’d attached to the tractor. His mind was not on the work he was doing. He slipped on some ice and grabbed at the spinning blade. The blade sliced through his mitten and cut very deeply across his right hand including the bones, especially of the thumb, the forefinger, and the long finger. Holding his hand, which fortunately was not bleeding badly, he walked back to the house. His daughter-in-law Helen took him to the hospital. There he passed out following a shot. Dr Retallack, who had served in the Pacific theater during World War II, at first thought he would have to amputate the fingers but he sewed the hand back together. The hand eventually healed although Victor had to write left-handed for a while and his thumb always remained a little stiff.

After she had settled her affairs in Sweden, Jenny sailed to the U.S. in June or July of 1948. In August, Victor and Jenny toured the midwest to visit relatives. Alida came west from New York and Victor drove them in his Model A Ford to Tracy, Minnesota, where Victor’s uncle Otto and some cousins lived. Next they went to Kenora where they visited with Carl, Anna, and Maria.

Victor cultivated a field to the north of the house. He had a small Allis Chalmers tractor with which he plowed and disked and cultivated and pulled the stone sledge. He planted potatoes and grain in the field. He also planted an orchard of about 15 apple trees between that field and the road. Near the orchard he had a patch of rubbarb. South of the house Jenny planted a vegetable garden that included corn, blueberries and strawberries. That garden was cultivated with a three pronged hand-pushed cultivator mounted on a single metal wheel the size of a bicycle wheel. Later they got a gaggle of geese, who wandered freely around the farm and left their droppings everywhere.

During the late 40s and early 50s, the mining companies searched for new sources of rich ore in Iron County. Planes were sent to trail magnetometers behind them to try to map the hidden iron. Many diamond drill holes were sunk to sample the rocks. Friday, July 15, 1949, a serious accident occurred at a drilling site located in the woods near 28 Lake on Victor’s farm. Three men were preparing to blast a boulder that obstructed their drilling when they accidently attached a live wire to a fuse and set off 10 sticks of dynamite. The explosion blew apart the trailer in which they were working and killed two of the men immediately. The third man managed to crawl part of the way a nearby drilling site but he died that evening. The search for iron continued, but in the end no major ore bodies were found. Over the course of the next two decades all mining operations in Iron County were closed down.

In the 1950s, a family tradition which Jenny helped to start was to spend Christmas eve at Victor’s house. His son Carl and daughter Greta always came with their families. Often daughter Aurora would return from Duluth by bus. Jenny cooked old world foods including flat bread, Swedish meat balls, whole fresh baked ham or roast turkey with decorated drumsticks, cranberry sauce mashed potatoes, lute fish, and salt cod. Greta and her husband Murray would also bring venison and tossed salad. The grandchildren ate in the dining alcove in the kitchen and the elders ate at the dining room table. After dinner was over and the dishes cleaned, the French doors to the living room were opened and everyone would exchange gifts around the Christmas tree. Finally there would be pie and coffee.

During summer of 1956 Victor and Jenny sailed back to Sweden for another visit.

As cars were designed to go faster and faster and as the highways were improved to handle the high-speed cars, Victor had trouble adjusting to them. Two stories illustrate this. In the early 1950s he was riding in the back seat of Carl’s car on a trip to Marquette to visit his grandson, who was in the hospital. Carl’s car had four doors. The doors in front opened forward, but the ones in back opened backward, unlike for modern cars. While on the road Victor decided that he needed to spit so he opened his door a crack to do it. The air rushing past the car caught the edge of the door and flung it wide open, nearly tossing Victor out of the car on to the shoulder of the road. The second story tells how he would park his car on the highway while he waited for Jenny to come out from visiting Mrs Matson, who lived in a house beside US2 about a half mile from Victor’s home. In the late 1950s a traveling salesman came up upon Victor’s car suddenly and hit it from behind.

In August 1960, Victor was forced to cancel at trip to Kenora with Jenny and his sister Maria because of a terrible pain in his right foot and leg that made it feel numb and cold. The condition continued to worsen through the fall. He was unable to undress or lie under the covers of his bed and the pain was so bad that he would throw himself up and down and scream. The foot swelled and turned many colors - red, blue, and white - and felt as though electrical shocks were being applied. Eventually doctors could do nothing except amputate the leg. This was a severe blow to him as he had always been very strong and robust. After the amputation, he was hospitalized for a long time, first at St. Mary’s hospital in Marquette and later at the Iron County Hospital near Crystal Falls. Yet even there he still could sing. His strong voice could be heard all the way to the basement. Eventually, he improved enough to return home, where he was in a wheel chair by August 1962.

He remained unhappy about being an invalid. In January 1963, he wrote that he had “no news, because I don’t see anything, hear anything, will nothing, don’t understand, don’t expect any!” In January 1966, he wrote that his “ 87th birth went painless and I feel as usual, but I know I stand on the ’Edge’...”.

In November 1967, his left leg was amputated. The shock was too much for him and a few days later he died. His physician again was Dr Retallack.

With age, Jenny grew less able to care for her home so, about four years after Victor’s death, she sold it to Carl Beauchamp and returned to Sweden. She lived with her brother William Soderstrom at Strömstad near the Norwegian border, until she died in February 1976.

VII. The Children of Victor and Frida

Victor and Frida had four children - Svea born in Sweden in 1906, Aurora and Carl born in Kenora, near Lake of the Woods in Canada, in 1911 and 1913 respectively, and Greta born in Port Wing, Wisconsin, in 1920.

After Frida died in 1928, the girls had to keep house, probably reluctantly. So whenever Carl infringed upon their clean floors, they were apt to chase him with a broom or throw a scrub brush at him. When the living room was cleaned, the door was locked and no one entered.

SVEA

Svea’s obtained a practical education. She received an award for her penmanship from Rogers School in 1924 and a certificate in bookkeeping from Stambaugh High School in 1926. She got a job at the Verona Mining Company office located near Caspian. One morning she was hit by a car while walking to work, but she survived.Svea married Alec Passamani in April 1936. He was the son of the Austrian couple who lived at the southern end of Passamani Road, where Victor had built his home. Alec also worked at the Rogers Mine. Alec built a cabin for them to live in next to Victor’s house. They had no children. In 1946 Svea became ill, maybe with cancer, and then shot herself with a rifle. Alec never remarried.

Svea was buried in the Bates Township Cemetery near her mother.

AURORA

Aurora wrote a brief memoir of her early days. She had a long and serious illness as a child, and recovered due to her father doing something extraordinary.There are many unknowns about Aurora. In June 1926 when 15 years old, she was staying with the Sundin family in Iron Mountain. Why? She was back at home in 1928 and attending school when her mother died. It was said that she left home at age 17, but the 1930 census counts her as being there with her father and siblings. Her photo album shows a boy friend named Wallace who was in the CCC. What happened to him? In 1940, she visited New York, Aunt Alida, Cousin Peggy, and the World’s Fair. She also visited Washington, D.C., possibly on the same trip. I haven't found her in the 1940 census. Where did she live then?

In the early 1940s, she exchanged letters with Ernest West, who was a private in the Army’s 1st Infantry Regiment. He trained at Fort Meade, Maryland. In late 1943, he was sent to North Africa and then to Italy.

At one time she worked in a restaurant in little Brule, Wisconsin. In 1942 she moved to Duluth where she knew a family and took a job as a waitress in the Hong Kong Cafe on West Superior Street. In November 1946 she married Russell Hovey in a Methodist church in Duluth. They had no children and were divorced in Oct 1958. Russell got married again the following spring but Aurora never did.

In 1975 Aurora became a member of the First Covenant Church of Duluth and soon after moved into senior citizen housing about two blocks from where she had been living. She had her own small apartment and liked the combination of freedom and security that her new dwelling provided.

In the mid 1980s Aurora moved from the senior citizens apartment into a nursing home because she was experiencing depression and could not care for herself. Here she shared a small room with one other woman so she had to store and eventually dispose of many of her belongings. The place also had no air conditioning even though it received the direct, hot sun in the summer. Still she was happy because she made many friends, especially among the staff, many of whom treated her like a mother or grandmother. She also enjoyed making crafts and selling them at fairs held by the nursing home. At this time she ate heavily and gained weight. Eventually her weight and weak knees kept her from walking. In April of 1987 she entered a hospital because of shortness of breath and feelings of anxiety. On May 5 she returned to the nursing home. Two days later she again complained of shortness of breath and then died suddenly of congestive heart failure in the afternoon. She was buried out in the country in Union Cemetery.

CARL

Carl married twice, once to Betty Seehase in 1936 and once to Helen Nault in 1942. He and Betty had a son Charles (1936). He and Helen had four children - Albert (1943), Carl (1947-2019), Terri (1952), and Wayne (1960). Carl settled only a quarter mile from his father’s house. He died in March 1975 of a heart attack. Carl’s story is told more fully in the following chapters.GRETA

Greta married Murray Baker. Greta and Murray had three children - John Peter (1947), Catherine (1950), and James Curtis (1953). She died way too soon, just months after her brother Carl, and also of a heart attack. Greta’s story is told more fully in a following chapter.

Victor and Frida’s only son, Carl Gustav Victor Fritiof Holm, was born in Kenora, Ontario, on January 28, 1913. When he was four years old, his family moved to the copper mining town of Victoria, Michigan. The road from Victoria to any place else goes down a long steep hill into the valley of the Ontonagon River and then up again to Rockland. He would always remember how in the winter the younger men would ride homemade bobsleds into this valley and part way up the other side.

His older sister Aurora remembers walking to school in Victoria one day with him when a girl chased her down an embankment. Carl tried to protect her and chased after the other girl. They were five and seven years old at the time. Their home was somewhat isolated so the children would play together. One game they played was “house” with mud pies.

In later years Carl did not get along so well with his sister. One Christmas she and Carl got new sleds; she locked hers away and used his until it broke. Even then she would not share. Carl could not leave money or anything personal on top of his dresser or bed because Aurora would take it and not return it until he promised her half.

When Carl was six, the family moved again, this time to a farm near Port Wing, Wisconsin. There they acquired the Newfoundland dog, named Nigger, who would accompany Carl during the years he grew up. With his sisters, he attended South Shore Community School at Port Wing, riding to school in a covered wagon in the fall and spring and in a covered sled in the winter.

When Carl was ten, the family moved one more time, to a mining company house in Bates Township near Iron River, Michigan. In one story from the time he lived at Rogers, he was picking raspberries in an opening in the woods when he came nose-to-nose with a black bear. Both were surprised to meet the other and, fortunately for the smaller of the two, both left quickly in opposite directions.

Carl’s opportunities for encounters with bears were probably few because his father, Victor, wasn’t going to let his son become a lazy “good for nothing” like some of the other boys in the neighborhood. So hunting, fishing, and sports were out of the picture. There was too much work to be done from daylight to sundown. Victor was very regimented, probably due to his hardships and to his training in the Swedish army. Thus when Carl went fishing or roasting potatoes over a bonfire with friends, he had to sneak away.

While Carl was living in Bates, he had rheumatic fever as his father had in his younger years.

Carl attended grade shool and the first two years of high school at the Rogers school, which had been built in 1913 and 1914 for grades one through ten. This school had two floors and a basement with main entrances in the front (north) and on either side of the building. From each entrance a flight of stairs led up to the first floor where there were four class rooms and, at the south end, an auditorium. From the side entrances, additional flights of stairs went up to the second floor where four more class rooms and the school office were located and down to the basement where there were two class rooms, a kitchen and lunchroom, the heating plant, and, at the south end under the auditorium, a gymnasium. There was a storage attic above the auditorium, reachable from the second floor. A stairs from the southwestern, second-floor classroom provided a back entrance to the auditorium’s stage. An auxilliary entrance on the southeastern portion of the building provided additional access to the rear of the auditorium. A survey in 1928 showed that the school was in excellant condition, the equipment was complete, and the quality of teachers was commendable. With the good background obtained at Rogers, Carl transferred to the Iron River High School, which had been completed in 1928, for the final years of high school to get his diploma in 1932. He had the ability to go on to college and had wanted to become a county agricultural agent, but the family had no money and scholarships were not available. So those opportunities were out!

One summer Victor and Carl’s three sisters returned to Kenora for a family reunion. Carl was left behind to care for the family’s animals - a decision for which he was resentful for decades.

When he graduated from high school, the world was deep in the depression and jobs were hard to find, even in Iron River. On July 1, 1934, at age 21 Carl joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. At the time he enlisted he was 5 feet 7 inches and was given smallpox and typhoid vaccinations. At first he was stationed at Camp Sturgeon near Waucedah, in Dickinson County Michigan, where he helped to plant pine trees in the reforestation effort. Each month he sent home his whole pay check, $30. During this period he was absent without leave on December 8 and on January 21. On May 11, 1935, he was re-assigned to Camp Hoxeyville near Wellston, Michigan, where he worked as a cook. While at this camp he met Elizabeth “Betty” Seehase, a woman whose parents owned the nearest farm to the camp and from whom the camp got its water, and they began seeing one another. Finally, on January, 12, 1936, he was re-assigned to Camp Grayville in the southeastern corner of Illinois, where he helped repair soil erosion. He was discharged from the CCC on March 1, 1936, to accept a civilian job.

On May 2, 1936, Carl married Betty Seehase in Cadillac, Michigan.

IX. The Seehase FamilyThe Seehase family came to America in 1871 from Lünburg, Hannover, in northern Germany on the Intermediate Deck of the S.S. Thuringia. The immigrants were Henry (or Heinr) Seehaase and Sofia (Bertke) Seehaase, with their 8-month-old daughter Dora. Henry was born around 1843 and died at a young age in 1884. In Chicago he worked as day laborer. Sofia was a seamstress, but a 1887 Chicago city directory also said that she sold cigars and a 1888 city directory said she was a grocer. She died in 1905. Henry and Sofia had two sons. The first was named Charles, the first in a series of Charleses, who was born around 1872. Their second son was William, who was born in 1880. The 1920 and 1930 census reported that, as an adult, William Seehase worked for W. W. Kimball as a piano maker. There is family lore that some in the family became associated with gangsters. A woman had a baby by Al Capone (1899-1947). A man was murdered in a gang-related event in Florida. I haven’t found records of these, but they aren’t likely to be widely publicized. Charles Seehase, also known as Whitey, worked as a piano and cabinet refinisher, but eventually purchased a saloon in Chicago. Rumors are that he was a very popular saloon owner. In April 1896, he married Barbara Malek. Barbara had been born in Bernadice, Bohemia, on September 25, 1877, and was brought to America by her parents Josef and Eleonora Malek with two brothers, Vaglan and Jan, when she was two years old. Her parents later had more children: Rose, Mary, Josephine, Earl and Jack. Charles and Barbara had two children, Charles Francis Nicholas and Henry. Henry died in 1904 at age 4. Then Charles died in Chicago in 1910. Family lore says that she married another man who then abandoned her, but I haven't found the records of this marriage. Barbara did move to Hoxeyville, Michigan, at this time. |

|

In 1917 Charles N. Seehase married Mildred “Millie” Sekanina. Millie was born in 1898 in Bohemia and came to America with her parents Vincent and Aneska Sackanina in 1901. They settled on a farm near Hoxeyville, Michigan. In 1930, his mother was living with them, and they had three daughters and two sons: Elizabeth “Betty”, Rose, Elsie, Jack, and Robert. In 1949 Charles opened a service station, but he died of a heart attack soon after in 1950. Millie died in Columbus, Ohio, in 1993. They both are buried in a cemetery near Dublin, Michigan.

X. Carl and Betty Holm’s Marriage, and Its Aftermath

Soon Carl and Betty married, his job disappeared so they moved north to Bates Township in the Upper Peninsula. Their son, Charles Victor, was born September 26.

It became apparent that they had few interests in common. One special item of disagreement was that she did not care for life in the Upper Peninsula. Around Christmas time they traveled to her parents’ home in South Branch Township where she decided to stay when he returned to the Upper Peninsula. In February 1937 he went back to try to convince her to return with him but to no avail so he returned north again on May fourth. In August 1937 she sued him for divorce. In the divorce papers, Betty said that he prefered the company of a woman he knew in Bates. However, there was no romantic interest, just that this woman shared his strong interest in reading. The divorce was granted on November 26 with custody of Charles being given to Betty and Carl being required to pay $3.50 per week for support of their son. Carl felt bad about this and really missed his son.

Betty (Seehase) Holm married again in February 1940 to a man whose name was Max Lewses or something like that. Her son, Charles, was left with his grandparents. They raised him and adopted him in 1950.

With the depression nearing an end, Carl found work in construction, first with Bocco Construction and later with Proksch Lumber. For Bocco he did road work on US2 west of Iron River, between Beechwood and Watersmeet. He began to smoke cigarettes at this time when he discovered that the workers who smoked were allowed time out to sit down with a cigarette but those who didn’t smoke had to keep working. For Proksch one of his jobs was wheeling cement in a wheelbarrow up ramps. This was in the days before cement mixers and was very hard labor. Not owning a car, Carl many times walked all the way home from work. There were times while he walked when his father Victor would drive past him - probably without even seeing his son trudging along - which made Carl angry.

In those days there were many eccentric characters in Iron County. One of them was Buckboard Charlie, an old bachelor who lived in a shack by Lake Emily. When road crew with which Carl was working stopped near Charlie’s shack for lunch one day, Charlie invited them in for a cup of hot coffee. When they accepted, he took some dirty cups off the table and rinsed them in a tub of water on the floor. The crew’s thirst for coffee quickly disappeared when Carl noticed that Charlie had his underwear soaking in the same tub in which he had washed the cups.

Working at Proksch, Carl could obtain slightly reduced prices on the material for the house he and Victor were building on Passamani Road. In addition, his paycheck went to the family. He was lucky to get work clothes out of the deal.

During this time Carl kept house for his dad. He would scrub the floors so they were bleach-white - until Victor would come in from the garden wearing muddy shoes. Carl also did the cooking. One of Victor’s favorite dishes was salt herring. Before cooking the herring must be soaked to remove the salt it was preserved in. But Victor had a habit that many other people have of salting all his food before even tasting it. This irritated Carl, who tried to make everything taste just right. So one time he didn’t soak the salt out of the fish at all but cooked it and served it as it was. Victor was perturbed and got red in the face, but the next time he had salt cod he tasted it first.

Carl also made home-made bread using an old fashioned bread pail, which had an arm attached to it for kneading the dough. The Passamanis, who lived at the end of the road, seemed to know when Carl was baking. They would drop by for a visit and always take a loaf or two when they went home.

After Proksch, Carl went to work as a cab driver for Vic’s Cab in Iron River for $20 a week. There he met Helen Nault, who was working as a dispatcher for Vic.

Then World War II came along. In April 1942, he was inducted for military service but was rejected because of a valvular heart condition and because of his 15/200 vision.

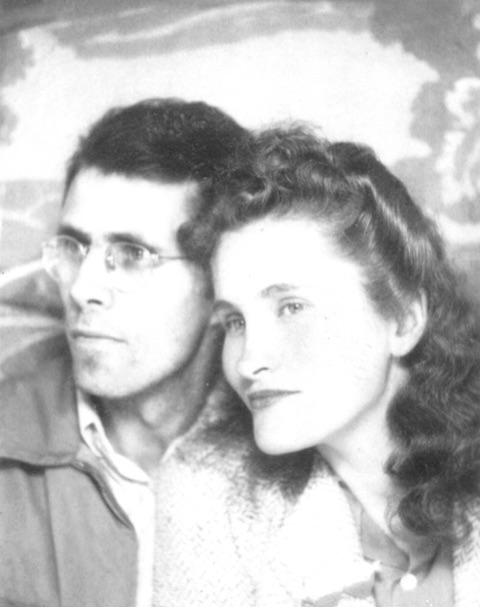

Carl married Helen Nault on June 27, 1942. Sam and Rose Nault, her adoptive parents, participated as the witnesses at the wedding.

Helen was born Hellen Exzine Fonder on January 11, 1924, in little Tipler, Wisconsin, to Cora (Green) Fonder. Cora was 28 years old at the time and was married to August J. Fonder. Among Cora’s ancestors were early immigrants to America. Cora’s mother was Ellen Herrick (1862-1921). One of Ellen’s great-great-great-great-great-great grandfathers, Henrie Herrick, arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony around 1629. Another great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather was Lieutenant William Palmer who arrived in the Plymouth Colony on or before 1639. She also had a Dutch ancestor, Hendrick Janszen Oosteroom, who arrived in New Amsterdam in the 1650s.

Cora’s father was Fred R. Green. Fred's parents were John Green (1800-about 1861) and Anna Hetzler (1813-1869). We don’t know John Green’s ancestors, but Anna Hetzler’s were German immigrants who lived near Rochester, N.Y. John and Anna had six children: Emiline (1830-1921), Dewitt (about 1835-1900), Fred (1839-1905), Elizabeth (about 1841-1899), John (1844-1845), and Anna (1848-1850).

John Green moved his family from New York to McHenry County, Illinois, around 1839. In January 1948, gold was discovered in the Sacramento Valley of California. In either 1849 or 1850 John GREEN became at “ 49er” and joined the trek across the Great Plains and the Rockies. He did not hit it rich, but was happy with the new country. Despite his requests for them to join him, John’s family never followed him to California. He died, maybe in the late 1850s or early 1860s. A family story is that John was murdered while trying to return to the east.

Anna was back in New York in 1860. She re-married there, but returned to Illinois when she died in 1869.

Cora’s father, Fred Green, was a soldier in the Civil War. He served in New York’s 160th Regiment in Louisiana. He married his first wife, Charlotte Chapins, in 1857. They had three children, John C. (1858-1904), Anna (1860-after 1903) and Frederick D. (1862-1924). While Fred was in the army, Charlotte grew unhappy with him and left the family, taking their daughter Anna with her.

In 1868 Fred remarried, to Harriet Harrington, a widow who was about 30 years old. She had two daughters Julia and Angeline, from her first marriage. Together Fred and Harriet had four children, Eveline (1873-?), Grace (1875-1927), Bert (1877-1947), and Mabel (1879-1939). Then Harriet died in 1883, leaving Fred with a young family.

Three months after Harriet died, Fred married Ellen Herrick. He was then 44 years old and she was only 20. Ellen’s mother, Nancy Ostrum, had died in 1878. Her father, Charles Herrick, had served in the 30th Wisconsin Infantry during the war and suffered from health problems as a result of his service.

Fred and Ellen Green had three daughters, Gertrude (1891-1922), Florence (1893-1912), and Cora, who was born on February 18, 1895. In 1896, the family with his children and their children moved to a farm in tiny Mountain, Wisconsin. Fred had a pension for injuries that occurred during his Civil War service, but that ended when he died in 1905. Cora was 9 years old then. Ellen tried to get a pension as a widow of a veteran, but it turned out that neither Fred nor his first wife, Charlotte, had obtained a divorce. Pension investigators found Charlotte living under a false name, “Fanny Parker”, in Missouri. Since the first wife was still alive, government did not recognize Ellen’s marriage. Therefore, there was no pension and the family fell into poverty. They went to live with her sister and then she married another Civil War veteran, James Jewell. Jewell soon died. Ellen’s second pension request was rejected. Then she died in 1921 at age 59.

|

August Fonder was not Cora Green’s first husband. She married Charles Close

in New Rome, WI, in March 1914. They moved to West Allis, WI, where the marriage went bad.

He claimed that she went out with other men and entertained them at home while he worked.

In May 1920, he divorced her. She was back in Mountain, WI, by then.

Cora married August Fonder in August 1921. She was 26 years old and he was 50. August had been married before, to Annie Myers, but she died in 1917. Neither Cora nor August had any children. August Fonder’s father, Augustus Fondaire, came from Belgium after the American Civil War and his mother, Exzina Poulin, came from French Canada around the same time. Cora and August moved to Tipler in Florence County. Their only child, Helen Exzine Fonder, was born there in January 1924. They moved to Iron River, Michigan, around February 1929, but August would not provide Cora and Helen with a place to live. She had to find their own lodging. Furthermore, August refused to live with them and returned to Mountain. Why did August abandon the family? No one now knows for sure, but there is now genetic evidence that Helen was not his daughter. If August knew or suspected that, he would have plenty reason to leave them. Being a good Catholic, he never divorced Cora. August died in March 1937 at Oconto Falls. If August wasn’t Helen’s father, who was? The DNA evidence points at a member of the Schroeder family, possibly Frederick Walter Schroeder who had been the husband of Cora’s sister Gertrude, who had died in 1922. Since Cora had no support, her five-year-old daughter was taken from her and placed in a foster home. Cora twice petitioned the court to get her daughter back, but was turned down each time. This last suit was filed in 1931 and rejected in 1933. After that, Cora disappeared from our view. |

|

On August 29, 1929, Helen was adopted by Sam and Rose Nault, a childless couple. She was given the new name Helen Mary Nault. Sam’s parents came from Quebec via Pennsylvania and Ishpeming, Michigan. In Iron River, they ran a residential hotel and tavern. Rose’s father, Louis Ducharme, came from Quebec and her mother, Emma, was American. They lived in Gibbs City. Emma died when her children were young, so Rose dropped out of school to care for her siblings when she was in 4th grade.

When they adopted Helen, Sam and Rose had a 60-acre farm west of Iron River. Helen did chores on the farm and attended the two-room Nash District School through fifth grade. Then she attended Central School in Iron River and later Iron River High School. She left school before graduating, and went to work for Vic’s cab company.

XII. Carl Holm and His Second Family

After Helen and Carl married, their first home was in Burns Addition, west of Iron River.

|

When Carl and Helen got their own home, Victor had to do his own cooking. On the

weekend he would make a large pot of soup, which he could eat for the rest of the week. He

would cook fish in brown paper over the coals in his wood range. When he cooked potatoes, he

would eat them off waxed paper to avoid having dishes to wash. Eventually he hired a Swedish

housekeeper, who cleaned up the house again, but she only stayed for a year or so.

Soon Carl left taxi driving and found a job in the construction of the Soo Locks. After six months there, he got another job at Lindahl’s lumber camp. On December 2, 1943, he and Helen had their first child, Albert. In Aug 1945 Carl and Helen bought 20 acres of land located kitty corner from his father’s farm. This was the southern end of Melvyn Matson’s land which fronted on US2 and stretched back along Passamani Road. In 1945, Carl answered an advertisment for work for General Motors in Lower Michigan which promised better pay than he could get in Iron River. He went ahead to try out for the job of an assistant electrian in a GM engine plant in Saginaw. Having won the job, he found a rented apartment in the second story of a two story home for his family. In March Helen took Albert on the bus downstate, and Carl met them in St. Ignace. But life in the city was not attractive to them. They decided they would return to Iron River, where Proksch had promised him a job anytime he returned. Then, in summer of 1947, a U.P. Lure book arrived in the mail. This soft-covered, magazine-sized book contained photographs of Upper Peninsula senic areas and resort advertising, and was intended to lure tourists into the north woods. They were soon on the bus going north again and later always joked that the Lure book had lured them. |

After they got back to Rogers, they moved into Victor’s home. Later Victor returned to Sweden for a visit of several months. Then, in October 1947, their second son Carl Jr. was born. The next summer, when Victor’s new bride Jenny arrived from Sweden, there wasn’t enough room in the old home. Carl and Victor began to construct a new house down the road on the land that Carl had bought from Matson. With two bedrooms, a kitchen, and combination living room-dining room it wasn’t big because they intended to convert it to a garage after building a larger home. But it was sufficiently finished that they could move in during the fall of 1948, even though they had to use an outhouse throughout the winter and take baths at Victor’s because the septic tank was not done.

In the old days, many working people helped make ends meet by farming one or two acres. Our friends the Demboski's kept cows in a shed behind the house, the Shamion's kept chickens, and grandpa Victor had geese as well as farm crops. One Friday evening in spring after getting paid, Carl helped old Martin Martinson who lived on US2 west of Rogers location to plow his small field. Carl drove Victor’s Allis-Chalmers tractor. While he was driving, his wallet fell out of his pocket and was covered over by the dirt from the plow. It was gone for good; a search revealed nothing. Years later, another plowing of the field brought the wallet back up to the top. It had decaying bits and pieces of the $50 still in it.

In November 1952, Carl and Helen had a daughter Terri Lee. They were still living in their “garage” which by then was too small. So the next summer they set about expanding it with the help of friends. They added a large room which nearly doubled the floor space. The new room had a fireplace and a concrete-block basement. The basement was always damp but it provided a lot of work and storage space. The exterior was covered with tar paper which always made it look a little unfinished.

In 1954 they sold two acres on the northeast corner of their land to Alfred Wodzinski in hopes that his children would provide playmates for their children. The Wodzinski’s and their children never did live there. Instead a house trailer on the lot was occupied by a succession of older people, the longest lasting of which was a childless Wodzinski sister.

Carl had worked for the Proksch Lumber Company since returning from Saginaw to Iron River. He worked every day of the week and half a day on Saturday. His skill with math helped to guarantee customers that they got the right amounts and sizes of the materials they needed. Often customers would seek him out rather than be helped by anyone else who was there. But in 25 years, Proksch never provided any vacation. Carl complained often about the working conditions and the management. He belonged to a hod carriers union which had a local in Iron Mountain but they never did much to help him get raises or benefits. Even so he strongly favored unions because many working people had suffered in the time before there had been unions.

He was a careful and conscientious worker. Still accidents could happen. Carl had long believed that Proksch’s band saw was dangerous; then one day while cutting a board for a customer he lost the tip of his little finger. He was taken to Dr. Retallack who sewed it up without benefit of anesthesia. Proksch never compensated him for this because there wasn’t enough off. The roots of the finger nail were still there so the nail would grow and have to be clipped.

Evenings and weekends he would sometimes help people with home construction work. He aided many in the area, such as helping putting a basement under Eino Kataja’s house, building Ray Johnson’s new house, and interior remodeling for Eddie Demboski.

Finally, in May 1972 he quit Proksch and went to work for Brandon Hill Supply, which was located west of town on US2. In October of that year, he bought Brandon Hill with two other men. Over the next several months, they began to build up the inventory to include lumber and renamed it the Hi-Way Lumber. Starting up the new business gave him a chance to try to do things the way he felt was best, but he and his partners had started with little capital and they always had a hard time keeping a sufficient inventory. During the following years Hi-Way Lumber continued to do business but it remained a stressful situation.

Early one July morning in 1974, Carl awoke with a pain in his chest. Taken to the hospital in Crystal Falls, he was found to have had a heart attack. He felt that this had brought on by the stress of his new business, that he could have handled the stress if he was even ten years younger but he was too old for it now. It took several months to recuperate from the heart attack. To build his strength, he took walks with the dog.

On March 14, 1975, Carl and Helen went for a ride on their snowmobiles, going east on the trail alongside US2. Snowmobiling was something they had started after most of the kids had left home and which they enjoyed during the long UP winter months. They went down Marinoff’s hill and up to Chicagoan Slough, but the snow wasn’t really deep enough and the bridge over the slough was bare. So around 8 PM they began to turn the machines around. Carl got off to push and collapsed. Helen flagged a car down and they drove him to the hospital but he was dead within minutes of the massive heart attack. He was buried in the Bates Township Cemetery next to his father, mother, and oldest sister.

Two years later, April 1977, Carl’s widow, Helen, married Greta’s widower, Murray Baker. The couple lived on Passamani Road. With the merging of the families, Murray and Helen were known as “Uncle Pa” and “Auntie Ma”. Among other things, they enjoyed camping, snowmobiling, and visiting with their families. Helen passed away in August 1997. After some years of living on his own, Murray moved into the Jacobetti Home for Veterans in Marquette, Michigan, where he passed away in May 2011.

XIII. Greta Holm, Murray Baker, and the Baker Story

Greta was the only one of her siblings born in the U.S. She went to Washington, D.C., for a while, but then returned to Chicago where she got a job in a factory which made cutting and grinding tools. Tuberculosis forced her to leave that job in the early 1940s and to live in the Pinecrest Sanitarium at Powers for about 3 years.

In 1943 Greta married Murray Baker.

According to Jack Hill’s book A History of Iron County Michigan, Murray’s grandparents, Elzeard (1845-1934) and Delvina (Bolduc) Baker (abt 1851-1931), were pioneers who settled in Stambaugh in 1886, coming originally from Sainte-Julienne, northeast of Montreal in Quebec Province, Canada. They were married on November 28, 1871. Their son Frank, the ninth of fourteen children, was the first baby of European descent to be born there.

Elzeard and Delvina’s children include Neil J Baker (1875-1949), Celia (Baker) Thompson (1877-1961), Eugene C Baker (1879-1967), Marie L. (Baker) O'Donnell (1881-1940), Rosanna (Baker) White (1883-1950), George R Baker (1884-1984), Joseph V Baker (1885-1947), Frank Baker (1886-1976), Nels Baker (1888-1935), John B. Baker (1889-1971), Ann Baker (died as a child), Jane M. (Baker) Thomas (1892-1982), and Amelia (Baker) Eddy (1895-1964).